Abstract

-

Purpose

This study aimed to analyze the multiple mediating effects of self-esteem, depression, and crisis coping on the relationship between disability acceptance and life satisfaction among older adults with disabilities, comparing periods before and during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic.

-

Methods

This study employed a longitudinal comparative design, using data from waves 1–5 of the Disability and Life Dynamics Panel. The sample was divided into pre-pandemic (2018–2019) and pandemic (2020–2022) periods. Roy’s adaptation model served as the theoretical framework. Multiple mediation effects were examined using the PROCESS macro (Model 6).

-

Results

Both the direct and indirect effects of disability acceptance on life satisfaction were significant, indicating partial mediation. In the pre-pandemic period, approximately 60% of the total effect was attributable to the direct effect and 40% to the indirect effect. During the pandemic, the proportion shifted, with the direct effect decreasing to 49% and the total indirect effect increasing to 51%.

-

Conclusion

In crisis situations such as a pandemic, self-esteem, depression, and crisis coping play crucial roles in improving life satisfaction among older adults with disabilities. These findings highlight the need for policy approaches that consider diverse socio-psychological factors to increase life satisfaction among older adults during pandemics.

-

Key Words: Attitude of disability; Coping skills; Depression; Personal satisfaction; Self concept

INTRODUCTION

South Korea is undergoing rapid population aging, bringing profound social and demographic changes. According to recent statistics, the country had already entered a super-aged society by 2024, and by 2050, older adults are projected to comprise more than 40% of the total population [

1]. The 2023 National Survey of Older Adults further revealed that functional limitations and disability-related challenges are becoming increasingly serious, with more than half of all registered persons with disabilities being older adults in that year [

2]. This indicates that aging among persons with disabilities progresses relatively faster than in the general older population and is accompanied by higher risks of physical and functional decline as well as secondary health conditions.

From an academic standpoint, the concepts of “aging with disability” and “disability with aging” cannot be regarded as identical or fixed; thus, a comprehensive research approach that captures their heterogeneity is necessary [

3]. Moreover, both domestic and international studies and policy frameworks generally follow the World Health Organization’s definition of the aging population as individuals aged 60 years and older [

4]. Previous research has also defined older adults with disabilities as individuals experiencing limitations in activities of daily living or restrictions in full participation in social roles [

5].

Older adults with disabilities face numerous challenges, including social, financial, physical, and psychological difficulties [

2,

6]. Thus, their average life satisfaction tends to be lower than that of individuals without disabilities and the general older population [

7]. Life satisfaction among older adults with disabilities encompasses their acceptance of their disability, maintenance of self-esteem and positive psychological states, and subjective evaluation of their lives based on their health status and available social and economic resources [

8].

Previous studies have identified disability acceptance as a crucial determinant directly influencing life satisfaction in older adults with disabilities [

9,

10]. Negative disability acceptance, which is defined as the inability to accept physical, mental, and social limitations resulting from disability, can lower self-esteem and heighten depression, thereby diminishing life satisfaction [

11]. Conversely, greater acceptance of one’s disability, regardless of its type, is associated with higher life satisfaction and enhanced self-esteem, reflecting a stronger sense of self-worth and personal value [

12]. Self-esteem and depression interact dynamically, jointly influencing life satisfaction [

12,

13].

In disaster and crisis situations, persons with disabilities are exposed to greater risks and stress due to the physical, informational, and environmental constraints associated with disability [

14]. Previous research has demonstrated that individuals with disabilities are disproportionately affected by disasters compared to the general population [

15,

16]. Crisis coping has been recognized as a mediating mechanism through which positive psychological resources contribute to life satisfaction [

17]. However, studies examining the impact of crisis coping on life satisfaction among older adults with disabilities remain scarce.

Disability acceptance [

12,

18], self-esteem [

12,

19], and depression [

18] have been reported as major factors that significantly influence life satisfaction among older adults with disabilities.

Older adults with disabilities are particularly vulnerable during health crises because they are often excluded from policy support. Inequality tends to worsen under such circumstances, leading to increased depression, social stigma, and discrimination, all of which further lower life satisfaction and self-esteem [

20,

21]. The recent health crisis triggered by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic resulted in widespread social isolation, mental health challenges, and economic instability, adversely affecting both the right to life and overall quality of life [

20]. Consequently, it has become a major cause of reduced life satisfaction [

22]. Historically, infectious disease crises such as the 2009 swine flu pandemic and the 2012 Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus outbreak have also had consistent negative impacts on general life satisfaction [

19,

23].

Life satisfaction is influenced by multiple interrelated factors, and these effects may vary depending on whether a health crisis is present. However, most previous studies on life satisfaction among older adults with disabilities have primarily focused on direct effects among variables such as social support, depression, self-esteem, quality of life, living environment, and economic status [

9], or on simple mediation effects. Yet, cross-sectional designs and simple mediation analyses are insufficient to capture the complex, multidimensional interactions among these factors or to explain how mediating effects differ under conditions of a health crisis [

24].

Therefore, longitudinal comparative studies are needed to identify and assess the various factors influencing life satisfaction among older adults with disabilities and to analyze the multidimensional interactions among these factors as they respond to evolving health crisis situations.

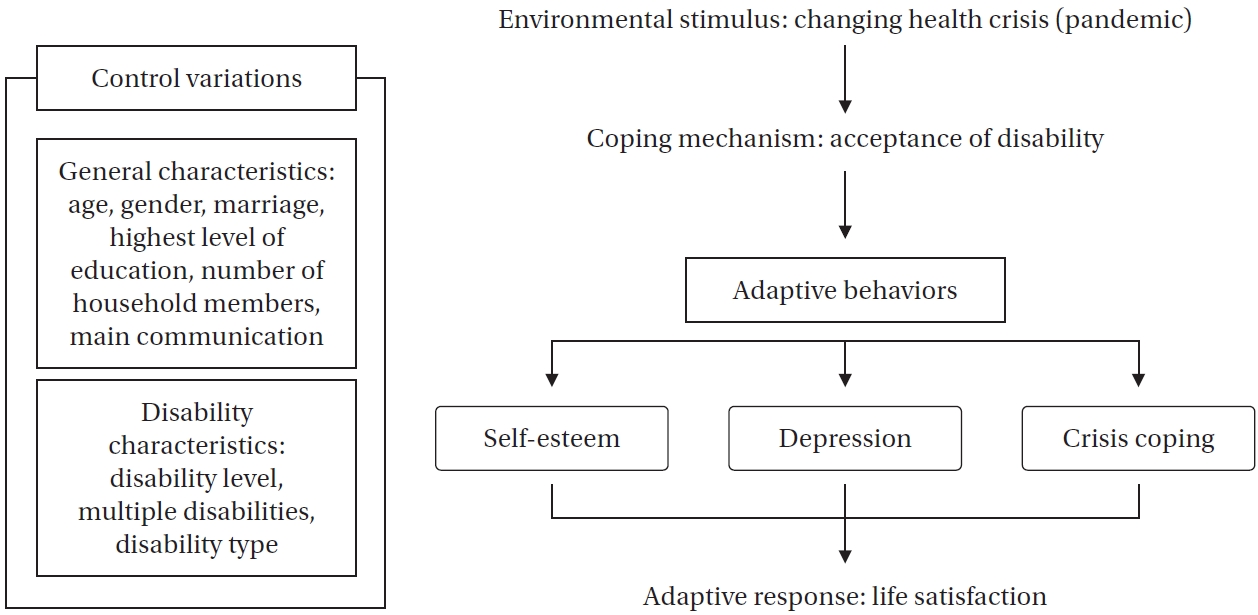

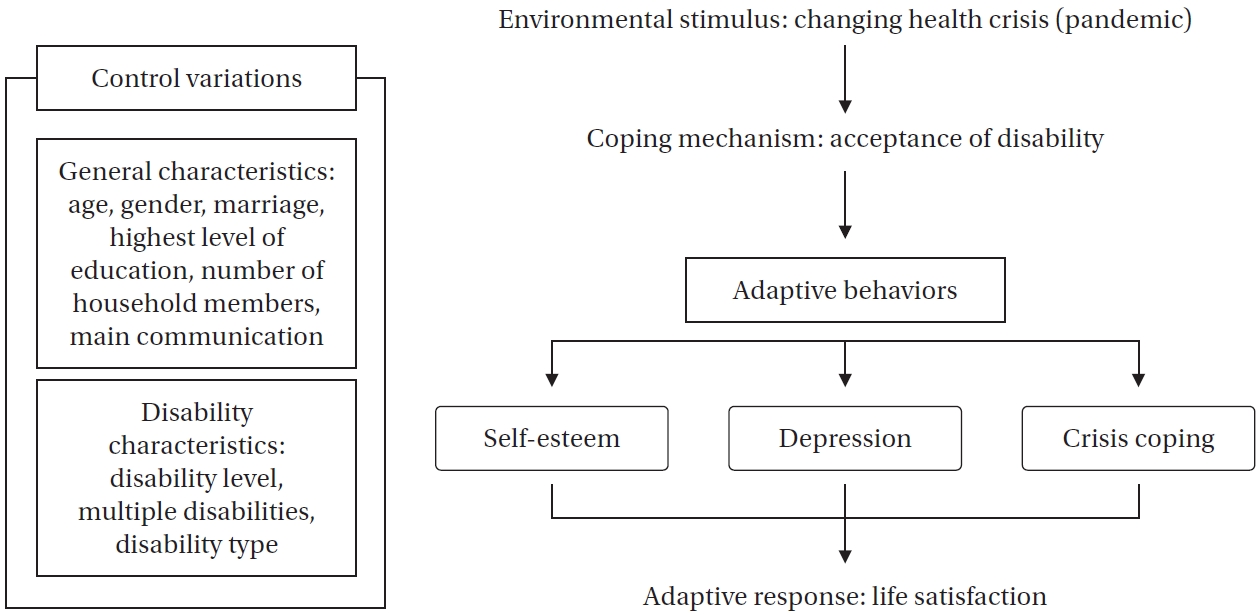

Roy’s adaptation model [

25] views human beings as living, open systems that interact with their environment and continuously adapt to changing stimuli. According to this theory, individuals employ a range of coping mechanisms to effectively adapt to environmental challenges.

Previous studies applying Roy’s adaptation model to infectious disease crises have conceptualized pandemics as external stimuli. Within this framework, individuals strive to achieve adaptive outcomes through coping mechanisms, which enhance their overall adaptability and capacity to respond to environmental stressors. These studies underscore the importance of adaptive processes in understanding the psychosocial and health-related responses of older adults with disabilities during a pandemic [

26,

27].

Through the lens of Roy’s adaptation model, shifting health crisis situations can be interpreted as environmental stimuli. Specifically, older adults with disabilities who previously existed in relatively stable coping environments before the pandemic may have relied on the adaptive mechanism of “disability acceptance” when confronted with the new environmental stressor of the pandemic. In this process, self-esteem, depression, and crisis coping may function as adaptive behaviors that ultimately lead to life satisfaction as an adaptive response. Furthermore, as Roy’s adaptation model aims to identify and regulate factors influencing adaptation to enhance life satisfaction, it provides an appropriate theoretical framework for exploring strategies to improve life satisfaction among older adults with disabilities (

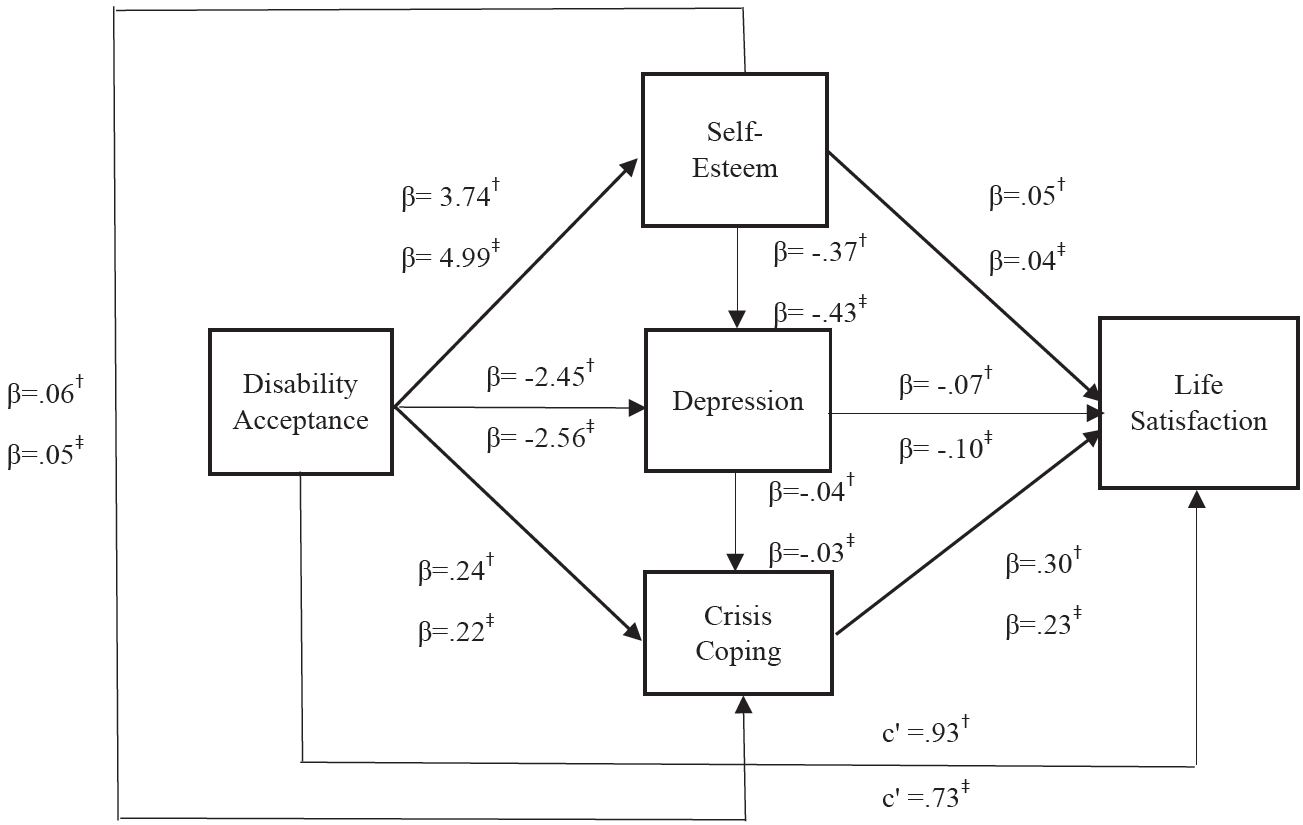

Figure 1).

Accordingly, this study seeks to analyze the direct and indirect—or multiple mediating—effects of self-esteem, depression, and crisis coping in the relationship between disability acceptance and life satisfaction among older adults with disabilities, comparing the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods within the framework of Roy’s adaptation model. The findings are expected to provide foundational data for developing policies that help older adults with disabilities effectively cope with future infectious disease crises.

The Disability and Life Dynamics Panel has continuously collected data on life satisfaction and related social and psychological factors among registered persons with disabilities from before the COVID-19 pandemic to the present. Therefore, conducting a retrospective secondary analysis using these data is expected to enhance both the efficiency and validity of the study.

METHODS

1. Research Design

A longitudinal comparative study was conducted using data from the Disability and Life Dynamics Panel collected between 2018 and 2022. The study compared and analyzed differences in the factors influencing life satisfaction among older adults with disabilities before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study is reported in accordance with the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines.

2. Research Data and Participants

1) Research data

Raw data from the Disability and Life Dynamics Panel were obtained from the Korea Disabled People’s Development Institute (KODDI) in accordance with its official data disclosure procedures. The panel was designed to establish foundational data for developing and supporting policies related to people with disabilities. Specifically, this study utilized data from the first survey (2018) through the fifth survey (2022).

2) Research participants

Participants were individuals with registered disabilities aged 60 years or older, based on an age classification reflecting the early aging characteristics commonly observed among people with disabilities. For analytical purposes, the data were divided into two temporal groups: the pre-pandemic period (2018–2019) and the pandemic period (2020–2022). The pre-pandemic dataset included 4,115 cases, and the pandemic dataset included 6,661 cases.

3. Measurements

The participants’ general characteristics included age, gender, marital status, highest level of education, number of household members, and primary mode of communication. The disability-related characteristics included the severity of disability, the presence of multiple disabilities, and type of disability. These variables were incorporated as control variables in the analysis.

To identify key influencing factors, variables were selected from the Disability and Life Dynamics Panel based on a literature review confirming their associations with life satisfaction. These included disability acceptance [

12,

18,

28,

29], self-esteem [

12,

18,

28], and depression [

12,

19]. Additionally, crisis coping was included as a variable that emerged as significant in this study. All variables were scored according to the User Guide of the 2024 Disability and Life Dynamics Panel [

29].

1) Life satisfaction

Life satisfaction was measured using eight subdomains developed by the Korea Welfare Panel Study team: health, income, housing environment, school life, occupation, marital life, social relationships, and overall life satisfaction [

29]. Each item was rated on a 10-point scale ranging from “had a very negative impact” (1) to “had a very positive impact” (10), with higher scores indicating a more positive perception of life. The reliability coefficient (Cronbach’s α) in this study was .96.

2) Disability acceptance

Disability acceptance was defined as recognizing and respecting one’s disability while maintaining a positive view of life. Kaiser’s (1987) Disability Acceptance Scale (DAS) [

30] was modified by adding three items addressing resilience and overcoming disability, resulting in a 12-item instrument used in this study. Each item was rated on a 4-point scale from “not at all” (1) to “very much” (4), with higher scores indicating greater acceptance of disability. The Cronbach’s α coefficient was .81.

3) Self-esteem

Self-esteem, defined by Rosenberg (1965) as a positive or negative attitude toward oneself, was measured using the Korean translation of Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem Scale [

31]. The instrument consists of 10 items, each rated on a 4-point scale ranging from “not at all true” (1) to “always true” (4). Higher scores indicate higher self-esteem. The Cronbach’s α coefficient was .76.

4) Depression

Depression was defined as the subjective level of depressive feelings experienced in daily life over the previous week. In this study, it was measured using the 11-item short form of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D-11) developed by the National Institute of Mental Health [

32]. Each item was rated on a 4-point scale ranging from “very rarely” (1) to “most of the time” (4), with higher scores indicating greater depressive symptoms. The Cronbach’s α coefficient in this study was .90.

5) Crisis coping

Crisis coping was measured using a tool developed by KODDI researchers to assess individuals’ awareness of appropriate response measures in crisis situations [

29]. The instrument consists of six items covering knowledge and abilities related to reporting emergencies, alerting others, locating emergency tools, using fire extinguishers, moving to evacuation shelters, and recognizing crisis situations. Each item was rated on a 4-point scale ranging from “extremely unable” (1) to “fully capable” (4), with higher scores indicating higher crisis response ability. The Cronbach’s α coefficient in this study was .94.

The Disability and Life Dynamics Panel utilized the Ministry of Health and Welfare’s national database of registered persons with disabilities as its sampling frame, ensuring a 95% confidence interval (CI) for national representativeness. Data collection was conducted through one-on-one, in-person interviews performed by trained professional interviewers with individuals with disabilities living in the community (not residing in facilities) and their household members. Sensitive information was collected through self-report questionnaires to maintain anonymity. The survey content covered five major areas—general status, disability acceptance and changes, health and medical care, independence, and social participation—comprising more than 280 items [

29].

The panel employed a double sampling method, in which towns and rural districts were first selected to ensure proportional representation in the final sample. Data collection occurred annually in the second half of each year, tracking the same participants longitudinally. Although data were anonymized annually, the sample retention rate exceeded 85%, supporting the panel’s validity for longitudinal analysis [

29].

This study is a retrospective secondary analysis using existing panel data, making it impractical to obtain individual informed consent. Accordingly, the dataset was requested and obtained through KODDI’s official anonymous data request procedure. All data were anonymized prior to analysis, and stringent measures were taken to protect participants’ privacy and personal information. This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Sahmyook Medical Center with which the primary researcher is affiliated study (date of approval: 2025/03/31; No. 116286-202503-HR-02).

6. Data Analysis

All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS/WIN Statistics ver. 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The general and disability-related characteristics of participants were analyzed using frequency analysis, and group homogeneity was verified using the chi-square test. Differences between the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods in disability acceptance, self-esteem, depression, crisis coping, and life satisfaction were assessed using the independent samples t-test. Correlations among variables were examined using Pearson’s correlation analysis. Hierarchical regression analysis was employed to sequentially introduce independent and mediating variables while controlling for confounding effects. Finally, path analysis was performed using Hayes’s (2022) PROCESS Macro for SPSS (ver. 4.2, model 6) to test multiple mediation effects of self-esteem, depression, and crisis coping on the relationship between disability acceptance and life satisfaction.

RESULTS

1. Participants’ General and Disability-Related Characteristics

In the analysis of participants’ general and disability-related characteristics, significant differences between the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods were found in age (

p=.028), highest level of education (

p<.001), main mode of communication (

p<.001), and disability level (

p=.021). However, gender, marital status, number of household members, multiple disabilities, and disability type did not show statistically significant differences between the two periods (

p>.05) (

Table 1).

The differences in variables by period are presented in

Table 2. Disability acceptance was lower during the pandemic than before it (t=0.67,

p<.001). Self-esteem was higher during the pandemic than pre-pandemic (t=–13.32,

p<.001). Depression was lower during the pandemic than before the pandemic (t=20.13,

p<.001). Crisis coping was higher during the pandemic than pre-pandemic (t=–7.08,

p<.001). Life satisfaction was also higher during the pandemic period compared with pre-pandemic (t=–15.34,

p<.001).

In addition, the perceived impact of disability on life decreased during the pandemic compared to the pre-pandemic period; however, this difference was not statistically significant (

p=.27). Evaluations of family relationships (

p<.001), family health (

p<.001), emotional support and assistance (

p<.001), perceptions of social networking services (SNS) (

p=.015), the extent of daily living assistance required due to disability (

p<.001), and economic hardship (

p<.001) all increased during the pandemic compared with pre-pandemic. Nonetheless, these variables showed low correlations with the independent variable of this study—acceptance of disability—in the correlation analysis (r≤|0.30|). The variables showing moderate or stronger correlations are summarized in

Table 2.

Life satisfaction was significantly correlated with all variables during both the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods (p<.001). It was moderately positively correlated with disability acceptance (r=.36, p<.001; r=.40, p<.001) and and self-esteem (r=.31, p<.001; r=.38, p<.001), with stronger correlations during the pandemic than pre-pandemic. Depression showed a moderate negative correlation with life satisfaction (r=–.41, p<.001; r=–.51, p<.001), and the magnitude of this negative correlation was greater during the pandemic. In contrast, the correlation between life satisfaction and crisis coping (r=.33, p<.001; r=.33, p<.001) remained stable across the two periods.

3. Differences in the Factors Influencing Life Satisfaction Before and during the Pandemic

For the hierarchical regression analysis, general and disability-related characteristics were first controlled, followed by the inclusion of disability acceptance as the independent variable in the second step. In the third step, the mediating variables (self-esteem, depression, and crisis coping) were introduced.

Multicollinearity was tested prior to regression analysis. The tolerance values ranged from 0.43 to 0.99, exceeding 0.1, and the variance inflation factors ranged from 1.01 to 2.33, not exceeding 10, in both periods. Additionally, the Durbin–Watson statistic was close to 2, confirming no autocorrelation among residuals.

The influence of general and disability-related characteristics on life satisfaction in the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods was significant (F=22.83, F=32.03) in Model 1. After controlling for these characteristics, the influence of disability acceptance on life satisfaction was also significant (F=35.35, F=56.44) in Model 2. When self-esteem, depression, and crisis coping were added (Model 3), the model remained significant (F=52.39, F=104.22) (all p<.001).

The explanatory power for life satisfaction in Model 1 was higher before the pandemic (adjusted R²=15.0%) than during it (adjusted R²=13.4%). In Model 2, explanatory power was equal for both periods (adjusted R²=22.2%). In Model 3, the explanatory power during the pandemic (adjusted R²=36.7%) exceeded that of the pre-pandemic period (adjusted R²=31.8%) (

Table 2).

The independent variable (disability acceptance) and mediating variables (self-esteem, depression, and crisis coping) collectively explained 31.8% of the variance in life satisfaction pre-pandemic and 36.7% during the pandemic—an increase of 4.9 percentage points. These findings indicate that self-esteem, depression, and crisis coping are important variables in explaining life satisfaction.

4. Multiple Mediating Effects of Self-Esteem, Depression, and Crisis Coping

Because multiple regression analysis identifies only direct effects, it may yield inaccurate results when mediation effects are present. Examining the paths of mediating variables allows for the identification of direct, indirect, and total effects, thereby offering a more comprehensive understanding of causal mechanisms. Based on the premise that disability acceptance influences life satisfaction through self-esteem, depression, and crisis coping, mediating paths were analyzed before and during the pandemic using Hayes’s (2022) PROCESS Procedure for SPSS version 4.2 (model 6).

A multiple mediation model was constructed to evaluate the effect of disability acceptance on life satisfaction. To rigorously assess indirect effects, bootstrapping was applied with a 95% CI. The results are presented in

Table 3.

In both the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods, disability acceptance had a significant direct effect on life satisfaction (p<.001). Its indirect effects through the mediating variables (self-esteem, depression, and crisis coping) were also significant (p<.001). Thus, disability acceptance exerted a partial mediating effect on life satisfaction via self-esteem, depression, and crisis coping.

During the pre-pandemic period, the total effect (t=24.60, p<.001), direct effect (t=14.62, p<.001), and total indirect effect (B=0.62, 95% CI=0.55–0.70) were all positive and significant. The path-specific indirect effects (95% CI=0.01–0.23) were likewise significant, as the CIs did not include zero.

During the pandemic period, the total effect (t=35.84, p<.001), direct effect (t=16.10, p<.001), and total indirect effect (B=0.77, 95% CI=0.71–0.83) were also positive and significant. The path-specific indirect effects (95% CI=0.01–0.02) remained significant, as the CIs excluded zero.

Before the pandemic, approximately 60% of the total effect of disability acceptance on life satisfaction was direct (B=0.93), and 40% was indirect through mediating pathways (B=0.62). During the pandemic, this ratio shifted, with the direct effect (B=0.73) decreasing to 49% and the total indirect effect (B=0.77) increasing to 51%. Therefore, during the pandemic, disability acceptance exerted a stronger indirect influence on life satisfaction through complex psychological mediating processes than it did before the pandemic (

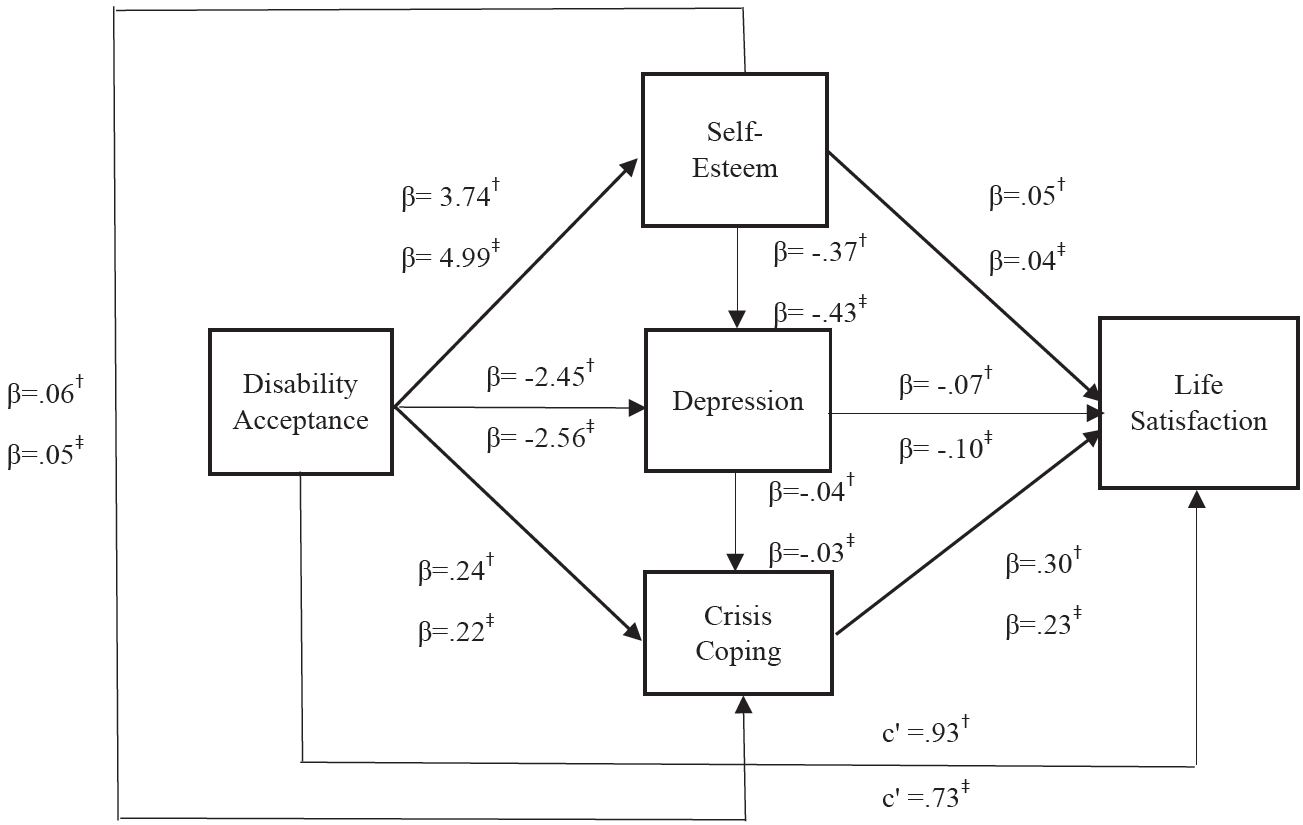

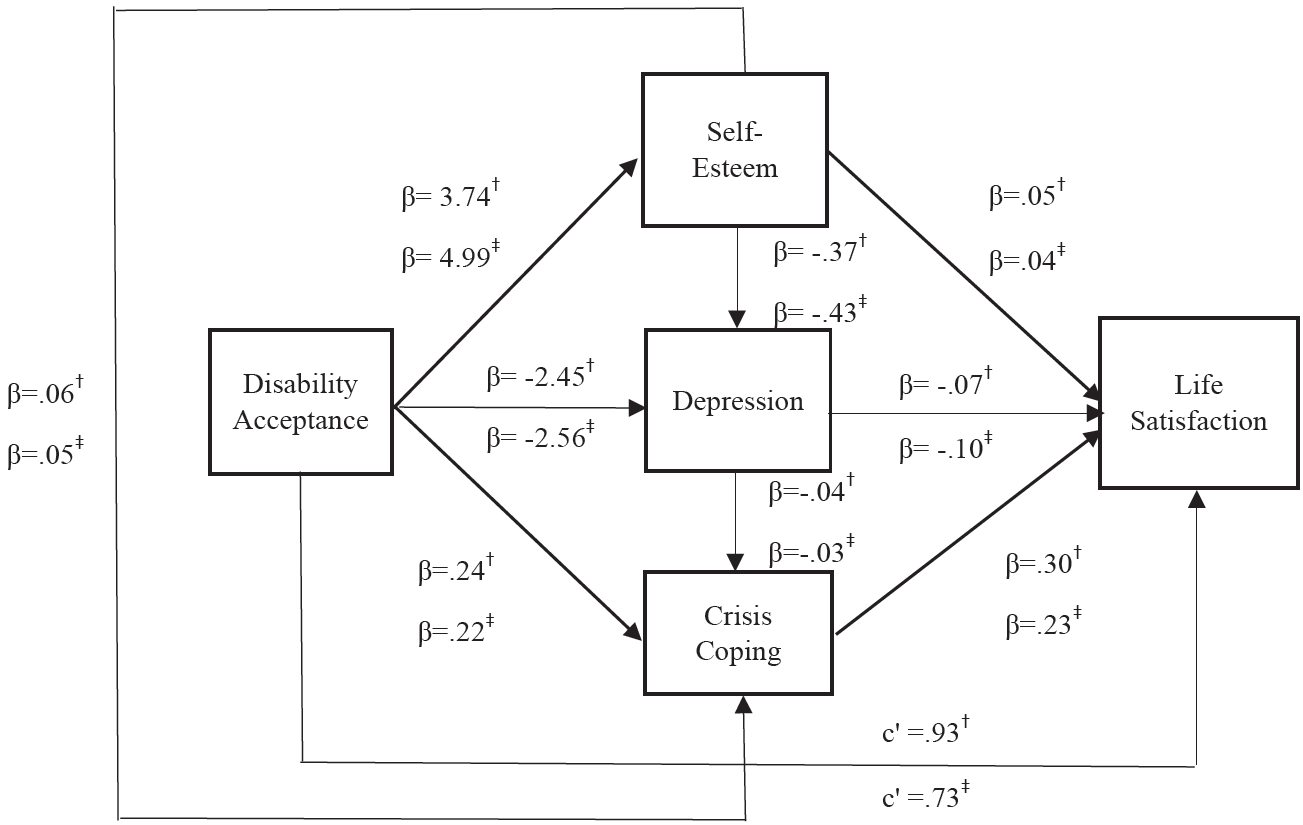

Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to analyze differences in the multiple mediating variables influencing life satisfaction among older adults with disabilities before and during the pandemic, using data from the Disability and Life Dynamics Panel. According to Roy’s adaptation model, individuals employ various coping mechanisms to effectively adapt to environmental stimuli. In this study, we examined the extent to which disability acceptance—conceptualized as a coping mechanism—affected life satisfaction (response) among older adults with disabilities before and during the pandemic, which functioned as a health crisis and environmental stressor. The mediating roles of self-esteem, depression, and crisis coping were considered as adaptive modes within this framework.

Older adults with disabilities encountered the pandemic as an environmental stimulus and, through positive disability acceptance, enhanced their life satisfaction by fostering higher self-esteem, reducing depression, and improving crisis coping. These findings provide foundational data for developing policies to help older adults with disabilities effectively adapt to environmental stressors such as future pandemics. Based on the major findings, the following section discusses the factors influencing life satisfaction during the pandemic and the mediating variables identified, while comparing them with previous research where applicable.

First, the dependent variable—life satisfaction among older adults with disabilities—was higher during the pandemic than in the pre-pandemic period. This finding contrasts with previous studies [

33] reporting that pandemic-related challenges, including social isolation, economic hardship, limited access to medical services, and increased psychological stress, tend to reduce life satisfaction. Guan et al. [

34], however, found that despite social restrictions, strengthened bonds with family, community, and neighbors contributed to improved life satisfaction among older adults, supporting the current results. Therefore, in the context of a pandemic, it is essential to consider the varying patterns of life satisfaction changes based on the characteristics of the target population when developing policy approaches. A few strategies include providing individualized care services, encouraging social interaction, and enhancing crisis coping abilities.

Second, self-esteem among older adults with disabilities was higher during the pandemic than pre-pandemic, and the mediating effect of self-esteem was statistically significant. These results differ from studies suggesting that self-esteem decreased due to heightened discrimination and inadequate support systems during the pandemic, such as insufficient policy measures, poor information accessibility, and limited physical access to testing sites [

21]. In a study of individuals with mental disorders, the direct effect of disability acceptance on life satisfaction was insignificant, but a complete mediating effect through self-esteem was identified [

12]. Similarly, research on individuals with hearing impairments found that incorporating self-esteem into explanatory models significantly increased its predictive power for life satisfaction [

28]. Collectively, these findings support the conclusion that self-esteem plays an essential mediating role in the relationship between disability acceptance and life satisfaction. Therefore, the need for proactive policy interventions to enhance self-esteem among older adults with disabilities is highlighted in health crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Third, depression among older adults with disabilities decreased during the pandemic compared with pre-pandemic, and this reduction had a significant mediating effect on increased life satisfaction. This result contrasts with prior studies suggesting that the pandemic negatively impacted mental health and increased depression [

34]. Notably, while the prevalence of depression in South Korea rose during the pandemic, especially among adults under 50 years [

35], the present findings indicate a different pattern among older adults with disabilities. This aligns with studies reporting lower depression levels among individuals with disabilities compared with those without [

20]. Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that tailored depression reduction policies reflecting the characteristics of older adults with disabilities would be effective during health crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Fourth, crisis coping ability was significantly higher during the pandemic than before, and it also exhibited a mediating effect on life satisfaction. However, the strength of the relationship between crisis coping and life satisfaction weakened somewhat during the pandemic compared with the pre-pandemic period. Research on crisis coping among both people with and without disabilities remains limited. One study found that older adults with considerable limitations in instrumental activities of daily living faced difficulties in coping with crises. Nonetheless, optimism, a sense of mastery, and social support from family and friends were identified as key resources that enhanced coping capacity and improved life satisfaction during the pandemic [

17]. Overall, these findings correspond with the present results, which suggest that crisis coping functions as a mediating factor influencing life satisfaction. Therefore, there is a need to develop programs aimed at improving crisis coping to enhance life satisfaction in older adults with disabilities. The crisis coping tools used in this study did not include items specific to health-related crises such as infectious diseases. Therefore, developing new instruments that can assess coping mechanisms in health-related crisis contexts—including pandemics—is necessary.

Finally, the multiple mediation model indicated that the direct effect of disability acceptance on life satisfaction decreased during the pandemic, while the indirect effects through mediating variables such as self-esteem and depression became more pronounced. This supports previous findings by Shin et al. [

9], who argued that higher disability acceptance alone may not guarantee greater life satisfaction without concurrent social and environmental mediating factors. Accordingly, this study, grounded in Roy’s adaptation model, verified the adaptive process of older adults with disabilities confronting a pandemic as an environmental stressor through the identification of multiple mediating effects. Interventions designed to improve life satisfaction among older adults with disabilities in future infectious disease crises should therefore focus not only on enhancing disability acceptance but also on strengthening psychological support, including promoting self-esteem and alleviating depression. The findings underscore the adaptive nature of psychological processes and the complex interactions among disability acceptance, psychological resources, and life satisfaction under crisis conditions.

Based on the study results, several recommendations are proposed. First, while this study focused on psychological variables—namely disability acceptance, self-esteem, depression, and crisis coping—previous research has highlighted that social support, family relationships, economic status, health condition, social participation, and access to community resources are also important determinants of life satisfaction. Although sociodemographic and disability-related characteristics were included as control variables in the regression analysis, this approach may not have fully captured the complex interrelationships among these factors. Future studies should consider using structural equation modeling to more comprehensively examine the relationships between disability acceptance and life satisfaction in older adults with disabilities.

Second, quantitative research alone is insufficient to fully explain the real-life changes, challenges, and psychological adaptation processes of older adults with disabilities during pandemics. Future research should adopt a mixed-methods approach that integrates quantitative data with qualitative insights, such as in-depth interviews and focus groups, to enhance interpretive depth and inform evidence-based policy recommendations.

Third, while this study compared pre-pandemic and pandemic periods, the pandemic itself consisted of multiple response stages, including social distancing measures, mandatory mask-wearing, and vaccination campaigns. These social interventions likely influenced variations in life satisfaction. Accordingly, further research should examine the factors influencing life satisfaction at each stage and explore how changes in resilience contribute to its improvement.

However, this study has certain limitations. As data were collected during a single infectious disease crisis, the generalizability of findings to other crisis contexts may be limited. Additionally, the retrospective secondary analysis design introduces potential constraints related to data collection procedures. Moreover, due to the scarcity of previous comparative studies on life satisfaction among older adults with disabilities during health crises, it remains challenging to fully interpret the observed differences.

CONCLUSION

This longitudinal study compared the effects of disability acceptance on life satisfaction among older adults with disabilities before and during an infectious disease pandemic. It identified variations in self-esteem, depression, and crisis coping; clarified the mediating roles of these variables; and provided evidence to inform practical interventions aimed at improving life satisfaction in preparation for future public health crises. The main findings can be summarized as follows:

First, disability acceptance and depression significantly decreased during the pandemic compared with pre-pandemic levels, whereas self-esteem, crisis coping, and life satisfaction significantly increased. Second, in the pathway linking disability acceptance and life satisfaction, self-esteem, depression, and crisis coping demonstrated partial mediating effects, which were stronger during the pandemic than before. This finding highlights the heightened importance of socio-psychological factors in influencing life satisfaction during times of crisis.

-

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

-

AUTHORSHIP

Study conception and/or design acquisition - HK and SRS; analysis - HK; interpretation of the data - HK; and drafting or critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content - HK and SRS.

-

FUNDING

None.

-

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We thank Professor Ji-Sung Lee from the Department of Medical Statistics, Asan Medical Center, Seoul, for assistance with the interpretation of the analyzed data.

-

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data used in this study can be obtained from the Disability Statistics Data Portal (https://koddi.or.kr/stat/html/user/main/main).

Figure 1.Conceptual framework: Roy’s adaptation model.

Figure 2.Paths of the mediating effects of major variables on life satisfaction. β=indirect effect; c'=direct effect; †Pre-pandemic; ‡Pandemic period.

Table 1.General and Disability Characteristics

|

Variables |

Categories |

Pre-pandemic(n=4,115) |

Pandemic period(n=6,661) |

Total(n=10,776) |

χ2 (p)

|

|

n (%) |

|

Age |

60–69 |

3,241 (78.8) |

5,363 (80.5) |

8,604 (79.8) |

4.86 (.028) |

|

≥70 |

874 (21.2) |

1,298 (19.5) |

2,172 (20.2) |

|

Gender |

Men |

2,211 (53.7) |

3,608 (54.2) |

5,819 (54.0) |

0.19 (.659) |

|

Women |

1,904 (46.3) |

3,053 (45.8) |

4,957 (46.0) |

|

Marriage |

No |

139 (3.4) |

252 (3.8) |

391 (3.6) |

1.52 (.469) |

|

Yes |

2,671 (64.9) |

4,271 (64.1) |

6,942 (64.4) |

|

Others |

1,305 (31.7) |

2,138 (32.1) |

3,443 (32.0) |

|

Highest level of education |

Primary |

1,138 (27.7) |

1,684 (25.3) |

2,822 (26.2) |

28.20 (<.001) |

|

Middle |

979 (23.8) |

1,570 (23.6) |

2,549 (23.7) |

|

High |

1,239 (30.1) |

2,237 (33.6) |

3,476 (32.3) |

|

College |

79 (1.9) |

158 (2.4) |

237 (2.2) |

|

University |

293 (7.1) |

492 (7.4) |

785 (7.3) |

|

Master’s |

37 (0.9) |

60 (0.9) |

97 (0.9) |

|

Doctorate |

9 (0.2) |

20 (0.3) |

29 (0.3) |

|

No education |

341 (8.3) |

440 (6.6) |

781 (7.2) |

|

Number of household members |

1 |

1,007 (24.5) |

1,595 (23.9) |

2,602 (24.1) |

0.66 (.884) |

|

2 |

2,020 (49.1) |

3,276 (49.2) |

5,296 (49.1) |

|

3 |

677 (16.5) |

1,128 (16.9) |

1,805 (16.8) |

|

≥4 |

411 (10.0) |

662 (9.9) |

1,073 (10.0) |

|

Main communication |

Sign language |

63 (1.5) |

61 (0.9) |

124 (1.2) |

93.51 (<.001) |

|

Writing |

87 (2.1) |

35 (0.5) |

122 (1.1) |

|

Gesture |

114 (2.8) |

124 (1.9) |

238 (2.2) |

|

Incomplete speech |

642 (15.7) |

970 (14.7) |

1,612 (15.1) |

|

Complete speech |

3,145 (77.0) |

5,378 (81.6) |

8,523 (79.8) |

|

Augmentative and alternative |

36 (0.9) |

25 (0.4) |

61 (0.6) |

|

Disability level |

Severe |

1,845 (44.8) |

2,835 (42.6) |

4,680 (43.4) |

5.36 (.021) |

|

Mild |

2,270 (55.2) |

3,826 (57.4) |

6,096 (56.6) |

|

Multiple disabilities |

Yes |

235 (5.7) |

430 (6.5) |

665 (6.2) |

2.44 (.119) |

|

No |

3,880 (94.3) |

6,231 (93.5) |

10,111 (93.8) |

|

Disability type |

Physical and sensory |

298 (20.9) |

4,840 (72.7) |

7,828 (72.6) |

13.82 (.387) |

|

Internal organ |

906 (63.6) |

1,445 (21.7) |

2,351 (21.8) |

|

Develop/mental |

221 (15.5) |

376 (5.6) |

597 (5.5) |

Table 2.Descriptive, Correlations, and Regression Models for Factors Influencing Life Satisfaction

|

Variables |

M±SD |

r (p) |

|

Disability acceptance |

Self-esteem |

Depression |

Crisis coping |

Life satisfaction |

|

Pre-pandemic (n=4,115) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Disability acceptance |

2.34±0.38 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

Self-esteem |

25.73±3.48 |

.41 (<.001) |

1 |

|

|

|

|

Depression |

21.97±6.41 |

–.23 (<.001) |

–.26 (<.001) |

1 |

|

|

|

Crisis coping |

2.98±0.90 |

.23 (<.001) |

.23 (<.001) |

–.32 (<.001) |

1 |

|

|

Life satisfaction |

4.73±1.65 |

.36 (<.001) |

.31 (<.001) |

–.41 (<.001) |

.33 (<.001) |

1 |

|

Pandemic period (n=6,661) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Disability acceptance |

2.28±0.43 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

Self-esteem |

26.70±3.94 |

.55 (<.001) |

|

|

|

|

|

Depression |

19.44±6.28 |

–.33 (<.001) |

–.37 (<.001) |

1 |

|

|

|

Crisis coping |

3.10±0.80 |

.31 (<.001) |

.37 (<.001) |

–.32 (<.001) |

1 |

|

|

Life satisfaction |

5.23±1.62 |

.40 (<.001) |

.38 (<.001) |

–.51 (<.001) |

.33 (<.001) |

1 |

|

Model |

R2

|

Adjusted R2

|

B |

F |

p

|

Durbin–Watson |

|

Pre-pandemic (n=4,115) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Model 1 |

.16 |

.15 |

5.01 |

22.83 |

<.001 |

1.89 |

|

Model 2 |

.23 |

.22 |

1.43 |

35.35 |

<.001 |

|

Model 3 |

.32 |

.32 |

2.37 |

52.39 |

<.001 |

|

Pandemic period (n=6,661) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Model 1 |

.14 |

.13 |

5.58 |

32.03 |

<.001 |

1.95 |

|

Model 2 |

.23 |

.22 |

2.84 |

56.44 |

<.001 |

|

Model 3 |

.37 |

.37 |

4.06 |

104.22 |

<.001 |

Table 3.Verification of Significance of Mediation Effect

|

Path |

Effect (B) |

BootSE |

95% CI |

p

|

|

Pre-pandemic (n=4,115) |

|

|

|

|

|

Total effect |

1.55 |

0.06 |

1.43–1.68 |

<.001 |

|

Direct effect |

0.93 |

0.06 |

0.81–1.06 |

<.001 |

|

Total indirect effect |

0.62 |

0.04 |

0.55–0.70 |

|

|

DA>SE >LS |

0.18 |

0.03 |

0.12–0.23 |

|

|

DA>D>LS |

0.18 |

0.02 |

0.14–0.23 |

|

|

DA>CC>LS |

0.07 |

0.01 |

0.05–0.10 |

|

|

DA>SE>D>LS |

0.10 |

0.01 |

0.08–0.12 |

|

|

DA>SE>CC>LS |

0.05 |

0.01 |

0.04–0.06 |

|

|

DA>D>CC>LS |

0.03 |

0.00 |

0.02–0.04 |

|

|

DA>SE>D>CC>LS |

0.02 |

0.00 |

0.01–0.02 |

|

|

Pandemic period (n=6,661) |

|

|

|

|

|

Total effect |

1.50 |

0.04 |

1.42–1.58 |

<.001 |

|

Direct effect |

0.73 |

0.05 |

0.64–0.82 |

<.001 |

|

Total indirect effect |

0.77 |

0.03 |

0.71–0.83 |

|

|

DA>SE>LS |

0.18 |

0.03 |

0.13–0.24 |

|

|

DA>D> LS |

0.25 |

0.02 |

0.21–0.29 |

|

|

DA>CC>LS |

0.05 |

0.01 |

0.04–0.07 |

|

|

DA>SE>D>LS |

0.23 |

0.01 |

0.18–0.23 |

|

|

DA>SE>CC>LS |

0.06 |

0.01 |

0.04–0.07 |

|

|

DA>D>CC>LS |

0.02 |

0.00 |

0.01–0.02 |

|

|

DA>SE>D>CC>LS |

0.01 |

0.00 |

0.01–0.02 |

|

REFERENCES

- 1. Ministry of the Interior and Safety. Population over 65 years old recorded 20% [Internet]. Sejong: Ministry of the Interior and Safety; 2024 [cited 2025 May 29]. Available from: https://www.korea.kr/briefing/pressReleaseView.do?newsId=156667293

- 2. Lee MK, Kim SH, Oh OC, Oh MA, Kim JH, Hwang JH, et al. 2023 Survey on the status of persons with disabilities. Sejong: Ministry of Health and Welfare, Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs; 2024 November. Report No.: 2023-132.

- 3. Era S, Katsui H, Kroger T. From conceptual gaps to policy dialogue: conceptual approaches to disability and old age in ageing research and disability studies. Soc Policy Soc. Forthcoming 2024 Mar 8. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746424000058

- 4. World Health Organization (WHO). Ageing and health [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2025 [cited 2025 September 15]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health

- 5. Mouchaers I, Verbeek H, Kempen G, van Haastregt JC, Vlaeyen E, Goderis G, et al. The concept of disability and its causal mechanisms in older people over time from a theoretical perspective: a literature review. Eur J Ageing. 2022;19(3):397-411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-021-00668-w

- 6. Lim JM, Yang EJ. The impact of disability onset timing on financial retirement preparedness of older adults with disabilities: a moderating effect of assets. Health Soc Welf Rev. 2024;44(3):182-201. https://doi.org/10.15709/hswr.2024.44.3.182

- 7. Park K. Life disparities between the disabled and the non-disabled and their policy implications. Health Welf Policy Forum. 2021;294:2-4. https://doi.org/10.23062/2021.04.1

- 8. Kim M, Ho SH, Kim H, Park J. Factors affecting life satisfaction among people with physical disabilities during COVID-19: observational evidence from a Korean cohort study. Ann Rehabil Med. 2024;48(6):377-88. https://doi.org/10.5535/arm.240056

- 9. Shin D, Kim Y, Kim G. The relationship between acceptance of disability and life satisfaction among older workers with disabilities in Korea: the moderating effect of workplace discrimination and education for disability awareness in the workplace. Disabil Employ. 2022;32(1):99-128. https://doi.org/10.15707/disem.2022.32.1.004

- 10. Kim HH. The impact of disability acceptance on life satisfaction: focusing on the mediating effect of self-efficacy and the moderating effect of the degree of participation in social activities. J Korea Soc Comput Inf. 2024;29(10):229-36. https://doi.org/10.9708/jksci.2024.29.10.229

- 11. Jung YH, Kang SH, Park EC, Jang SY. Impact of the acceptance of disability on self-esteem among adults with disabilities: a four-year follow-up study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(7):3874. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19073874

- 12. Choi JH, Hong SJ, Cha TH, Hwang HS. Effect of disability acceptance, self-esteem, depression, and human rights on quality of life of physically disabled people. Korean J Occup Ther. 2023;31(1):97-108. https://doi.org/10.14519/kjot.2023.31.1.07

- 13. Moon JY, Kim JH. Association between self-esteem and efficacy and mental health in people with disabilities. PLoS One. 2021;16(10):e0257943. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257943

- 14. Park EY. Factors affecting disaster or emergency coping skills in people with intellectual disabilities. Behav Sci (Basel). 2023;13(12):1018. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13121018

- 15. Demiroz Yildirim S. Integrated disaster management experience of people with disabilities: a phenomenological research on the experience of people with orthopedic disabilities in Turkiye. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023;88:103611. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2023.103611

- 16. Nordic Welfare Centre. Crises affect persons with disabilities harder: more accessible crisis preparedness is needed [Internet]. Stockholm: Nordic Welfare Centre; 2024 [cited 2025 September 15]. Available from: https://nordicwelfare.org/en/nyheter/accessible-crisis-preparedness-is-needed/

- 17. Xu D, Lalani N, Arling G. Coping and life satisfaction of older people during the COVID-19 pandemic. Innov Aging. 2022;6(Suppl 1):878. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igac059.3134

- 18. Choi HC. Effects of self-esteem and acceptance of disability on life satisfaction and depression in students with physical disabilities. Korean J Physical, Multiple, & Health Disabilities. 2023;66(4):75-93. https://doi.org/10.20971/kcpmd.2023.66.4.75

- 19. Lee M, Park R. The mediating effects of depression in a relationship between disability acceptance and life satisfaction of people with acquired disability. J Humanit Soc Sci 21. 2022;13(2):2315-28. https://doi.org/10.22143/HSS21.13.2.162

- 20. Kim Y, Nam J. The effects of COVID-19 on the mental health of the disabled. Health Soc Welf Rev. 2022;42(2):102-21. https://doi.org/10.15709/hswr.2022.42.2.102

- 21. Kim HM. Effects of self-efficacy, self-esteem, and disability acceptance on the social participation of people with physical disabilities: focusing on COVID-19 pandemic. Brain Behav. 2023;13(1):e2824. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.2824

- 22. Easterlin RA, O'Connor KJ. Three years of COVID-19 and life satisfaction in Europe: a macro view. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023;120(19):e2300717120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2300717120

- 23. Kanadiya MK, Sallar AM. Preventive behaviors, beliefs, and anxieties in relation to the swine flu outbreak among college students aged 18-24 years. Z Gesundh Wiss. 2011;19(2):139-45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-010-0373-3

- 24. Park SS. Influence of housing characteristics on health and life satisfaction of older adults. J Future Soc. 2024;15(2):70-88. https://doi.org/10.22987/jifso.2024.15.2.70

- 25. Roy C. The Roy adaptation model. 3rd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education; 2009.

- 26. Pickler L, Lima MM, Roque AT, Wilhelm LA, Curcio F, Guarda D, et al. Adaptation strategies for preparing for childbirth in the context of the pandemic: Roy's theory. Rev Bras Enferm. 2024;77(3):e20230159. https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7167-2023-0159

- 27. Imkome E, Moonchai K. Until the dawn: everyday experiences of people living with COVID-19 during the pandemic in Thailand. F1000Research. 2025;11:1560. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.127578.5

- 28. Park SH, Choi HC, Shin HJ, Kim YM, Park HJ. The relative effects of acceptance of disability and self-esteem on life satisfaction in people with hearing impairment. J Speech Lang Hear Disord. 2024;33(1):167-77. https://doi.org/10.15724/jslhd.2024.33.1.167

- 29. Kwak NY, Kim TY, Han JW. User guide for the disability and life dynamics panel (Waves 1-5). Sejong: Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs; 2024 May. Report No.: 24-02.

- 30. Kang YJ, Park JK, Gu IS. Validation of the self concept and self acceptance test for the people with disabilities. Seongnam: Korea Employment Agency for the Disabled Employment Development Institute; 2008 October. Report No.: 2008-05(1).

- 31. Lee J, Nam S, Lee M, Lee J, Lee SM. Rosenberg’ self-esteem scale: analysis of item-level validity. Korean J Couns Psychother. 2009;21(1):173-89.

- 32. Kohout FJ, Berkman LF, Evans DA, Cornoni-Huntley J. Two shorter forms of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression) depression symptoms index. J Aging Health. 1993;5(2):179-93. https://doi.org/10.1177/089826439300500202

- 33. Delgado-Rodriguez MJ, Pinto Hernandez F, Tailbot K. Has Covid-19 left an imprint on our levels of life satisfaction? Empirical evidence from the Netherlands. Heliyon. 2024;10(15):e35494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e35494

- 34. Guan Y, Jiang D, Wu C, Deng H, Su S, Buchtel EE, et al. Distressed yet bonded: a longitudinal investigation of the COVID-19 pandemic's silver lining effects on life satisfaction. Am Psychol. 2024;79(2):268-84. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0001188

- 35. Lee EJ, Kim SJ. Prevalence and related factors of depression before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: findings from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Korean Med Sci. 2023;38(10):e74. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e74